Shameless Note: My new book is the #1 New Release in Demography on Amazon based on pre-orders alone! Still trying to figure out how this works! I would be honored if you pre-order now as well!

This is an essay about lifestyle. But it has nothing to do with that Section in the New York Times designed to make you overspend on clothing, furniture, and housing.

My parents from the Silent Generation did not grow up with this concept - the notion of curating your own choices to life’s major decisions as if the past did not matter.

Austrian psychologist Alfred Adler coined the word “life-style” in 1929 (although some credit Carl Jung). He wanted to classify people in a way that would inspire them to be more adaptive to the modern world and its many social changes. His intent was progressive, but it was not scientific. It lacked any sense of prevalence.

“One of the purposes of Adlerian psychotherapy was to give the individual a more creative and less archaic and primitive approach to life. He claimed that whoever remains trapped in their feelings of inferiority and lack responds to their environment in a maladaptive way. In a hostile, dependent, or avoidant way.”1

When you read summaries of Adler’s Four “life-styles”, you can see that very few would fit neatly into his ideal - The Socially Useful Type.

Trump supporters sound a lot like his ‘hostile’ type. But I digress.

Adler’s theory implies that ‘most’ people in his era were not adapted to the modern world, let alone the future, in which individuals would independently decide most of their life decisions with minimal pushback from the broader society. In this world, divorce, hooking up, career change, etc., would be normal options. I’m not even sure Adler understood where social change was headed.

Adler’s approach is simplistic, but it was one of the earliest classification systems that detached itself from ethnicity, religion, and old markers of social privilege. The individual was now the unit of analysis. It was the center of our social concern: how do we make these old-fashioned individuals adapt to change for which no elders prepared them?

The word “lifestyle” in print is new…and started growing in the 1960s as lifestyle diversification accelerated exponentially. Hmmmm…

Figure 1. The Rise of Lifestyle Talk and the Decline of Railroad Speak

Lifestyles are cool, people. Railroads are for dead people and 19th-century novels. That’s what this chart tells us. I think.

More seriously, modern advertising and marketing took the idea of a “lifestyle” and spread it into everyday language. First, it appeared in Ad copy. Then, in common usage as we have come to live as advertisers nudge us to become.

Without the hyphen, lifestyle is now everywhere in our descriptions of individuals and consumer trends in ways that allow marketers to bucket relevant people together to form an audience.

The marketing definition is close to the medical one - they look at individual-level habits and their outcomes.

A junk-food lifestyle leads to diabetes and requires specific medical interventions.

A foodie lifestyle means you want spicy, ethnic packaged food, and it affects innovation pipelines in the food industry.

Our habits accumulate to form a lifestyle. This is the implication of this way of thinking.

If we all have hundreds of different habits, then each of us becomes analytically complex lifestyle snowflakes. Individuals have hundreds and hundreds of behavioral habits and un-examined consumer preferences (a forgotten choice we made long ago).

Most habits that persist unexamined in our lives are simply conscious choices we forgot we made long ago. Some of these habits are decades old (how I brush my teeth). Habit is simply a kind of choice made by our unconscious mind. It makes us knowable to other people, this predictability. Without habit, the individual goes mad and becomes insane to others.

Relationships are habitual choices, too, so breaking up is like overcoming a bad habit (!).

“Lifestyle” talk is a way of talking about choice if we can accept that choice is neither fully rational nor utterly conscious in every situation. The pretense we have is that we consciously choose our sexual partners. And our jobs. The reality is much murkier, even though we can point to the “choice” in retrospect.

A lot of the lifestyle differentiation between individuals is beyond trivial. It’s hard to get offended if I like Pepsi and you like Coke. Or if I like empanadas and you prefer pot pies. And if either is what constitutes a deal-breaking lifestyle choice for you, then make sure you never eat with your ‘friends.’ You probably don’t have any if you are this annoying.

But some of this lifestyle diversity, the big choices in life that affect our social networks, matter a lot.

Quantifying Change in Lifestyle Diversity

If we set aside the post-modern obsession with brand preference in hundreds of consumer purchase categories, we can more easily appreciate how much lifestyle diversification has occurred in the last half-century.

It’s a diversification of big and little choices in our lives.

Here’s a brief thought experiment from my forthcoming book about Lifestyle choice with a capital “L.” The big stuff.

As I mentioned, we do not consciously make all our life choices. If we did, we would go insane by late morning each day. And just because we perceive that a choice is possible does NOT mean we feel we have the power to exercise it. Historically in America, this state of adverse constraint has held for the poor, the black, the indigenous, the homeless, and women. The white male has always had more choices available to him in every given era.

Here are the stages of choosing stuff as an adult human (in any society):

Stage 1 – Perceiving a choice exists at all – before the 1970s, choosing not to marry was rarely perceived as a valid lifestyle choice; it was the reserve of priests, gays, mad men, and wealthy eccentrics (who literally could buy sex).

Stage 2 = Perceiving the full scope of possibilities – a conservative evangelical may understand that society will let them delay marriage. Still, they don’t see this as an option (because they’re horny yet don’t believe in fornication!). This may be due to family pressure or church ideology, or both, or a toxic set of hippie parents who magically reared their total lifestyle opposite. I had a roommate in college like this.

Stage 3 – Being open to part or all of the permissible scope – just because I know I can have an open marriage since adultery is no longer a crime does not mean I believe I am comfortable with this option or would ever bring it up with my wife even if I was. Which I’m not. As in ‘no.’

Stage 4 – Making a choice (at various levels of conscious awareness) – Marriage is a conscious and deliberate choice in all societies. What minimum level of food quality you adhere to at the supermarket is much less so.

Stage 5 – Accepting your choice – The therapists come in here! Don’t laugh. A lifestyle choice in America is not always one permanently made. The perception that even a marital choice is reversible (i.e., divorce) adds a modern level of anxiety to our lives. This is the stage in the choosing process that your parents or grandparents may still not understand (and many never will).

If I can force a review: Stages 1 and 2 are where cultural and familial influences linger from the past to varying degrees. Stages 3 and 4 reveal how much agency a person feels when making this or that perceived choice. Stage 5 is either straightforward or, increasingly, makes past choices maladaptive to a new present.

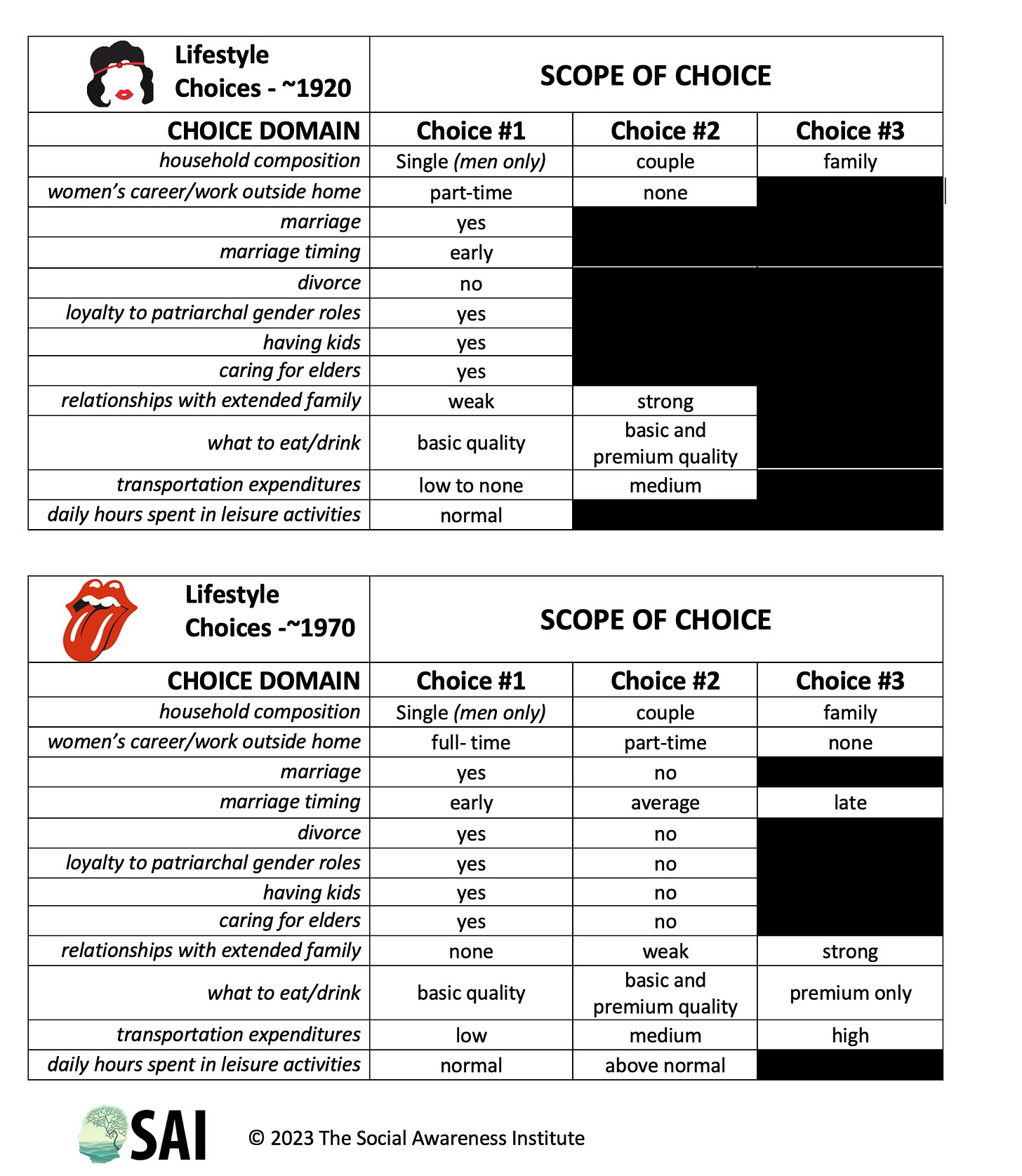

Now, let’s count up the scope of lifestyle choice available in 19020 and compare it to the scope of lifestyle choice in 1970 for a broad swatch of Americans.

What do we find?

HOW TO READ THESE EXCITING TABLES BELOW

Choice domain = a category of choice most modern Americans perceive as available

Scope of Choice = Was there a choice for most Americans, and how many?

Choice #1 = one possible choice widely known and perceived as available

Only one choice = most Americans could not exercise choice without fear of social reprisal

Just comparing the number of blacked-out cells in 1920 indicates the lower scope of choice for the average American.

But let’s do something more fun. Let’s turn these tables into some combinatorial math!

Let’s look at the options in the 1970s table and calculate the number of unique lifestyle choice combinations you get. There are 30 options across 12 mandatory choice domains, yielding 46,656 possible lifestyle combinations. Math is fun stuff. I’m sure there is a nerdy board game concept in here somewhere.

But, if we go back to 1920 and eliminate choices and options that the majority didn’t perceive, we only have six perceived choice domains available to most adults. There are fewer perceivable lifestyle choices and fewer feasible choices in this era (permissible without major social ostracization in a highly networked, more conservative society).

The choices available to most of America in the early 20th century yielded only 144 combinations or individual lifestyles.

From 1920-1970 Americans witnessed an exponential increase in lifestyle autonomy, from ~144 different lifestyles to ~46,000+. That’s a 324x increase in lifestyle options in just 2-3 generations.

This partial view of lifestyle change should help explain why you keep putting your foot in your mouth at those family gatherings and block parties. There are a lot of options out there. And a lot of ways to be confused or offended.

https://exploringyourmind.com/the-four-lifestyles-according-to-alfred-adler/

Thank you James for another amazing piece! Your work has been instrumental in my search for a wife. In my view, it’s incredibly important for men and women to minimize lifestyle diversity choices in order to better coordinate within marriage. Really appreciate your work!

Never really thought of it this way, that's really thought provoking in some ways, especially as I visited my grandma abroad the other day, and I thought about her life and _why_ she did and stayed "stuck" in the ways she is currently living, when she has so many other "lifestyle options" so to speak, and this might shed some light on that. ^^