Modern Flood Deaths Are A Failure of Imagination

And a lack of respect for nature

We all understand the difference between outdoor temperatures in the 70s, 80s and 90s. Our species probably evolved to notice these small differences with our skin because we have no fur and are warm-blooded, sensitive apes. Regardless of how, we’re sensitive to small air temperature fluctuations.

But how many of us can immediately envision the difference between standing in rain falling at 1/10th of an inch per hour, 1/2 an inch per hour or 1.5 inches and hour?

Did your eyes glaze over? Probably. These distinctions don’t click.

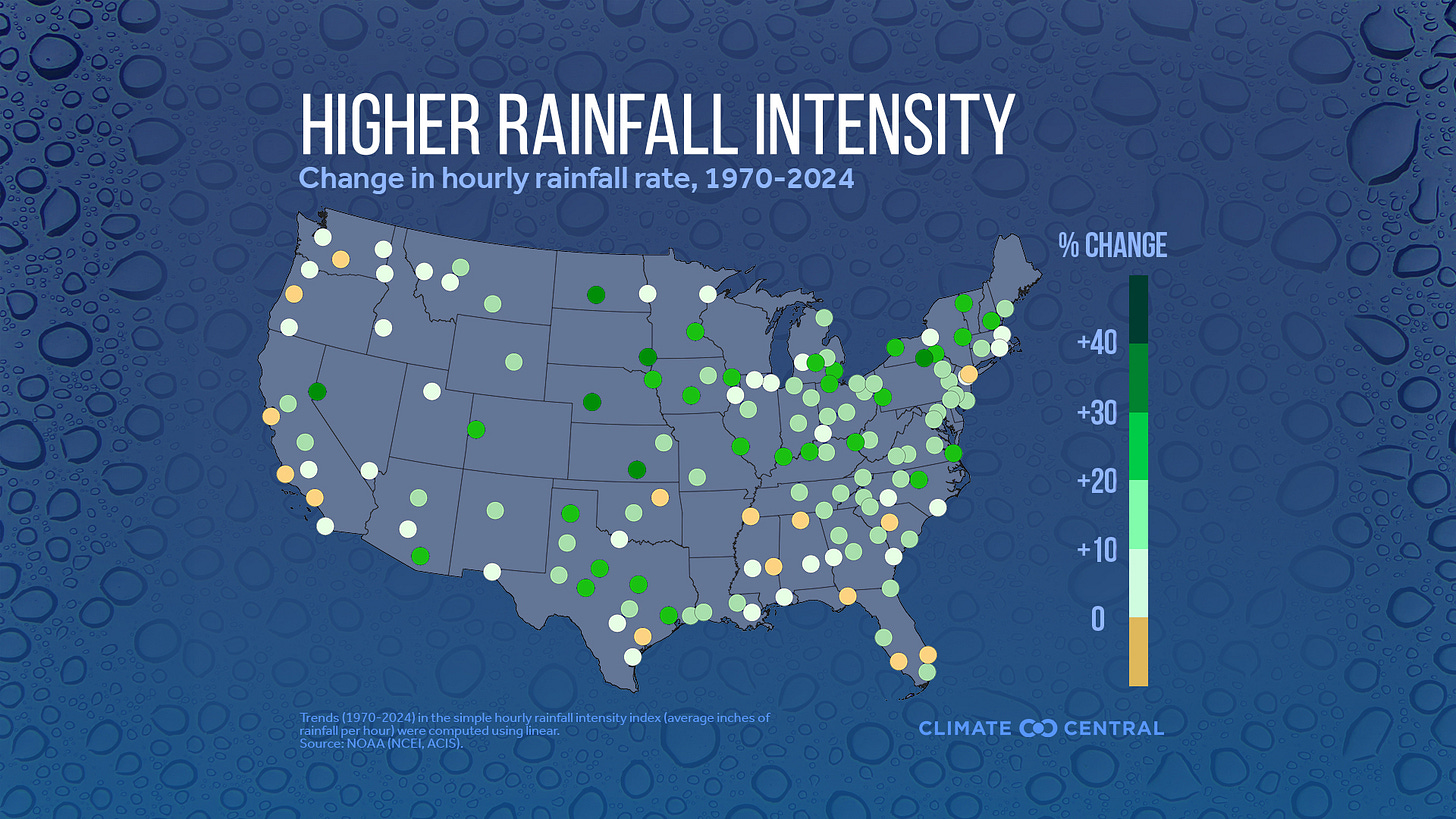

How many of you know that dozens of major metros in the United States have experienced a slow creep in average rainfall intensity in the past half century, including my current home town of Tucson?

How could any of us have noticed without a chart like the one above? We do recognize the increase in frequency of deadly flash floods, though. We notice the extreme outcome of the trend, not its root cause.

As the frequency of deadly flash flooding spreads across the country, even in unlikely places like rural Vermont and hurricane-smacked Asheville, NC, we have a choice as a nation.

Focus on imagining a difficult, unfolding future where nature has more authority

OR walk facing backwards as we dismiss the doomsayers

This choice comes down to our willingness to imagine our climate risks differently than we want to and differently than our personal memories support.

As American consumers, we are superb at living in the near future of the next new thing to consume, imagining all sorts of new, convenient technologies to acquire. Our consumer imaginations take us decades into the future with both excitement and ease.

So, why…is it so damn hard to imagine new risks in the near future?

Our test as a species in the 21st century will be to get over this pan-cultural, probably evolutionary, bias toward analyzing risk in the rear-view mirror but imagining opportunity we can not even see.

The government has a role in helping smack us out of our complacency, but, ultimately, as the Texas Floods just showed, we have to add this responsibility to our list of what it takes to be a modern adult.

Tucson: A Place Where Most of the Rain is Extreme

I have lived in Tucson, Arizona, for five years now. Anyone who has lived there for this long has likely experienced the Sonoran monsoon enough to alter their behavior around thunderstorms permanently.

I grew up in northern New England in the 1970s and 1980s and we had summer storms. The goal then was primarily to avoid getting wet. But, in a land of near endless, undulating young forests, we also learned not to stand next to trees during a storm. Anyone who hikes in New England has seen a blackened tree split open by a lightning strike. Ouch.

But, we New Englanders never once feared being carried away in our cars if we didn’t pay attention during a storm. And the roads never really flooded. Not all monsoon storms here in Tucson will deliver flash flood-inducing inundation, but most do, especially after the first two weeks of storms saturate the soil.

A monsoon storm owes its name to the unusually high moisture levels and extreme electrical energy in these thunderstorm cloud formations. The very strong downdrafts also create 40-60mph winds reliably. Patio furniture dances in the fresh mud.

Two weeks ago, our 2025 monsoon season kicked off at my home with a direct strike from a storm that dumped 3/4 inch of rain in about 20-25 minutes (!) That’s an hourly rainfall rate of 1.5-2 inches per hour. Fast.

This is what that rainfall rate looks like:

This is a common rainfall rate when a monsoon storm hits your location here in Tucson. However, since these storms often move quickly and the storm cells are very localized, you only have rain falling this hard for 20-30 minutes; sometimes less, if the storm’s edge is just grazing your location.

But we also occasionally have cells that shed 6-8 inches per hour inside their narrow cores. That looks more like this clip taken nearby - click image to watch.

Monsoon rain is micro-localized, intense thunderstorm activity.1 On an active day, Tucson may experience dozens of storms moving across the valley in waves. Many locations in the valley will receive only a few drops or nothing at all, as other small areas get hammered. This is what makes the monsoon particularly challenging for most Americans to comprehend. Summer storms in most of the country do not have as much moisture as these monsoon cells.

You don’t have to live in Tucson to experience this kind of intense rainfall rate, but the micro-localization of rainfall is very peculiar to a desert like ours. We do not get the enormous frontal lines of storms experienced in the Midwest that drench territory like someone pulling a squeegee across a massive windshield.

Tucson, specifically, lies in the heavy rain zone of the Southwestern monsoon, where 60% or more of our annual rainfall happens in just three months. Despite this climactic fact, micro-localization means that your property may only receive one direct hit a week at most. In other words, most of our rain is extreme rain by the rainfall rate standards of a typical US location.

“Did you get hit?” is a common text message question among friends and family spread around the valley. The question is highly relevant. A half mile distance could mean you are dry while your friend is getting hammered.

Look below at this cumulative rainfall map for the early 2025 Monsoon to understand what I mean by micro-localized rainfall. This map shows the total rainfall from our first three storm days of the 2025 monsoon season. The map is only 20 miles wide!

Here’s another way to imagine micro-localized rainfall - look how defined the rainfall spout is in the picture belwo. In fact, “spout” is a word you only hear in Tornado alley or here in the southwest.

Over the monsoon season, micro-localization of rainfall leads to very different seasonal totals from neighborhood to neighborhood. In 2021, for example, Tucson had a near-record-breaking monsoon with 12.79 inches (measured at the airport). However, at our home, 15 miles from the airport near the foothills, we received 17.5 inches! This rain all fell in three months…in a parade of thunderstorms that made for lots of child excitement.

The extreme seasonality of the desert monsoon means that we not only wait and wait and pray for rain, when it finally comes, it arrives dramatically and commands enormous respect. When scarcity and intensity combine, they tend to command anyone’s attention. Like the boys/girls dance at gender-segregated YMCA summer camps in the 1980s ( I pity the counselors who had to supervise that event).

What I’m pointing to is the fact that, for the average Tucsonan, summer rain is intense and dangerous, and it’s just a matter of when it hits your property—every year.

Imagine if you could guarantee experiencing greater than hurricane-level rain intensity once a week for two months every single year.2 Would you have a different orientation to “rain?” I think you would. And so we do in southern Arizona.

For us, “rain” isn’t banal, as in Seattle. It’s deadly business.

Most rainfall in the United States is far less intense and more evenly distributed throughout the year. It doesn’t come mostly in thunderstorms.

From 1959-2019, Arizona experienced 1/10th the flooding deaths of Texas, yet experienced almost twice as much population growth during this period and, today has almost 1/3 the population of Texas?3 We seem to be better at avoiding flash flood deaths with far worse public education.

On a related note, why did only a dozen people die in the Great Tucson Flood of 1983, our worst ever recorded urban flood in which thousands were displaced?

Our Choice Is an Imaginative One

Perhaps America needs to learn what Tucsonans have known since the first humans inhabited this valley.

We have to learn to imagine heavy rainfall as life-threatening, not just annoying. The opposite of complacency is not paralyzing fear. There is a middle-ground I’ll call a “healthy respect” for Mother Nature.

As so many of us have become ensconced in digitally interconnected, urban worlds, staring most of the day at screens (like I’m doing right now), we have learned slowly to discount nature’s power. We dismiss it and demote it.

Unlike atheism, though, this disrespect for supra-human power is a deadly trend that continues in America. It’s a bizarre form of willful ignorance and hedonic arrogance.

Sorry, too busy in the American funhouse to get worried!

When I researched a list of major flash flood incidents in the Tucson area, the vast majority involved people hiking into flood zones during the summer time or most likely homeless people living in washes.4

“Morons,” some of us would easily say. But, these deaths involve the extreme end of our broader disrespect for nature. If you’re high, young or both, your disrespect for nature is more likely.

The growing reality for Americans is that we need to view heavy rainfall forecasts more seriously than ever before. We need to have evacuation plans in place and practice them. We need to respect the need to shelter in place and not treat sheets of rain like an “adventure.” Not everything should be reduced to “fun.”

We have done this before. We now take hurricanes far more seriously than we used to. Katrina was a wakeup call.

In espionage, firefighting and law enforcement, they call the crucial skill required here - “situational awareness.” This concept came unconsciously to premodern humans living in a survival state. Situational unawareness got punished severely.

Situational awareness is a deeply personal responsibility for all of us, even if we also need government supplied weather data and alerts as an input. It is no longer just a professional ‘skill.’ Learn the decision-making cycle in the link above.

Lost in the current fingerpointing in Kerr county is the fact, released early on last weekend, that one camp - Mo-Ranch - evacuated before nightfall on July 3. They had an adult with strong situational awareness. They had a plan. It involved seeking higher ground even thought it would mean getting totally cut off (not a natural instinct for many). She wasn’t flipping through TikTok vids. She also appeared to have professional training in large conference planning.

There is no need for most flash flooding deaths when you look into the circumstances. They are not caused by dam breaks or unknown storms.

Lack of preparation is caused by mediocre imagination.

We simply have to imagine rain differently.

For a meterological deep dive, check out this article - https://extension.arizona.edu/sites/extension.arizona.edu/files/pubs/az1417.pdf

Some very smart scientists calculated the mean rainfall intensity for landfall hurricanes as 0.37 inches per hour. The flooding caused by hurricanes therefore happens slowly over many hours or days of sustained rainfall, not in 20 minutes. Source: DIFFERENCE OF RAINFALL DISTRIBUTION FOR TROPICAL CYCLONES OVER LAND AND OCEAN AND RAINFALL POTENTIAL DERIVED FROM SATELLITE OBSERVATIONS AND ITS IMPLICATION ON HURRICANE LANDFALL FLOODING PREDICTION Haiyan Jiang1 *, Jeffrey B. Halverson1 , and Joanne Simpson2 1 Joint Center for Earth Systems Technology, University of Maryland Baltimore County, Baltimore, MD, and Mesoscale Atmospheric Process Branch, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD 2 Laboratory for Atmospheres, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD - file:///C:/Users/pgs10/Downloads/108764.pdf

https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4441/13/13/1871; Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis - https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/AZPOP, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/TXPOP

https://www.library.pima.gov/content/flash-flood-deaths-in-the-tucson-area/

People have been dumbed down and many are waking around almost in a stupor , Sportball and social media have made people dumber

Hello James! I’ve been on here just over a week, and I’m trying to meet interesting new people, so I thought I’d comment.

I share a philosophical look into historic books, sharing what some call “alternative” history.

My latest article is about Tartaria:

https://open.substack.com/pub/jordannuttall/p/the-erasure-of-tartaria?r=4f55i2&utm_medium=ios