On Sept. 1, John Mackey, founder of Whole Foods Market, retired from the company he founded in 1980. For years, "Whole Foods" has been synonymous with the twin terms "organic" and "Whole Paycheck." Ironically, most individual items for sale there have never been certified organic, including most of the produce items. This has been true at Whole Foods since the federal government created a legal standard of identity for "organic" in 2002.

2002 was, incidentally, just about the time I entered this niche end of the consumer packaged goods industry as a consumer behavior research scientist. The first major consulting project I led involved a grueling national tour of Whole Foods Market's personal care department, known still as "Whole Body." Whole Body is the retail space to visit folks if you still want to see the craziest premium pricing in the grocery industry. It's the land of $20 shampoo, $10 toothpaste, and $150 probiotic supplement bottles. And it smells incredible because of the sandalwood incense section (why?) and the goofy cold-pressed soap bar (where you used to be able to cut your slice from a soap 'loaf'). Leaving a giant bread knife around in the open probably got the attention of legal and public health professionals. Yeah.

If I seemed to have drifted off into a description of some nostalgic hippie museum, hold that thought. The early pioneers of the 'organic movement' are folks like Gary Hirshberg (who went to the same private school I did!), the founder of Stonyfield Farms. Stonyfield still operates its Londonderry facility and was the first commercial organic yogurt brand with national distribution.

In its infancy, 'organic' was a cultural symbol more allied to Earth Day than it was to being a good, upper-middle-class mother. How did this symbol transition its locus of meaning that much in just a few decades? Was it an event? A 60 Minutes episode?

Part of the explanation lies hidden in the class origins of Mackey and his original team. Many do not realize Mackey was pretty much the textbook definition of a Baby Boomer' hippie,' although the Austin Texas sub-variant. His father was an accounting professor before becoming CEO of Lifemark, a network of 25 hospitals later sold to an acquirer in 1983 for $1B. This is the class context in which someone a(majors in religion in college, b) drops out, and c) starts a vegetarian co-op food store.

It's called a marine-grade safety net. Not something you’ll find in Montopolis.

And this kind of safety net allows creative minds to take significant risks inside their family AND in the public sphere. Class privilege also 'permits’ you to price your food shamelessly high to run what became the single most profitable, full-service grocery store chain ever. WFM earned a 3.2% net profit in 2017 before selling to Amazon.1 At the time, the average supermarket squeezed out maybe 0.5-1% in net profit.2 That's a 3-6x profitability premium. You can stop wondering why Wall Street loved John Mackey so much back then, despite his stock-price manipulation behavior in the Wild Oats merger (how do these people not go to prison?)

But, wait a minute. Organic was not the focus of Whole Foods Market originally. It was a vegetarian co-op.

Why?

For one simple reason: where the hell was the organic acreage under anyone's definition in 1980? And who was defining 'organic' anyway? John Mackey? By 2008, only 4 million acres came under the federal definition of 'organic,' still less than 1% of all agricultural land in the U.S.3

Organic - Origins of a Cultural Symbol

The initial interest in growing and harvesting 'organic' produce, dairy, and eggs emerged mainly from the after-effects of significant environmental studies and popular books based on them, such as Rachel Carson's the Silent Spring. These early environmentalists focused almost exclusively on the issue of chemical pollution in the open air, water, and land, including pollution from nuclear power plant waste.

Many today forget that the 1950s and 1960s were the peak acceleration of urban smog due to the persistence of leaded gasoline and poorly designed diesel truck engines. In farming, agricultural runoff, then and now, leaches unknown amounts of synthetic fertilizers and herbicides like RoundUp into local watersheds, including some public drinking water systems.4

Organic became an alternative farming movement, where farmers deliberately avoided using the toxic chemicals from the Bayer/Monsanto industrial chemical phalanx/cartel.

Organic farming has not succeeded as an agricultural movement. Just look at the % of the acreage. At 5.4 million acres in 2019, organic acreage is only 0.6% of total farm acres.5 Yes, you read that right. It makes me wonder if it is a USDA measurement error. I'm kidding.

Organic - the ‘Expensive Stuff’

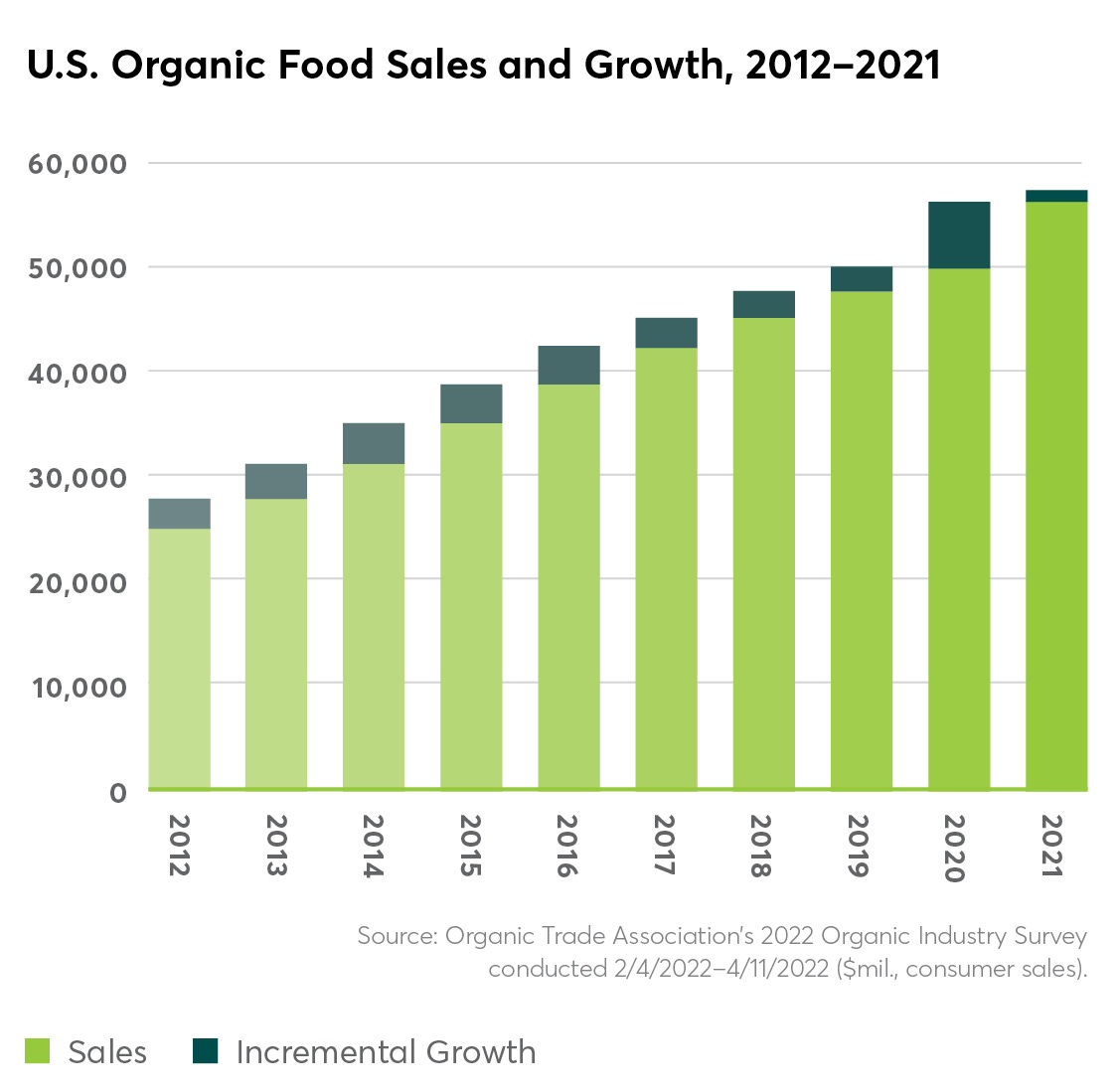

Regardless of the tiny amount of organic acreage, ‘organic’ food consumption is now a massive industry segment in the grocery universe. As of 2021, organic food (including milk) is roughly 7% of the $789B retail food pie. Wow.

Hmmm. 7% of retail food dollars. Yet only 0.6% of acres. This acreage-sales ratio would suggest some severe price premiums, which, of course, we all know very well. Traditionally, economists say this is a classic situation of supply not meeting demand and leading to the retail prices going sky high (because the motivated will pay these prices).

Or did organic farmers price in enormous profits from the start of the supply chain? Prior studies suggest that organic farming is 20-25% more profitable per acre than conventional farming (if you can get through the high costs of transitioning).6 Good for them.

Yet, specific farm commodities, like spinach and apples, have witnessed a rapid reduction in price premiums as demand scaled in the 2000s. Leading retailers are willing to suppress the retail premium for specific culturally high-value produce varietals and drive profitable traffic into their stores.

Yet, on average, American consumers don't easily part with even a 30% price premium on frequently purchased food items they enjoy. We're a nation whose consumer spending habits anchor culturally to spending little of our income on food (only 10%).

We believe it is our cultural right to pay little for food and virtue to seek out the lowest food pricing. The way even rich people celebrate food deals is really, truly strange (when you step back). My Dad (a not poor person) still marvels at how much food he gets off the Dollar Menu for $3 (even though he claims to his wife that he no longer goes there). Oops. One more cat out of the bag.

Food in this country is wrapped up in a complex morality of desperately seeking cheap sh*t. But we won’t go so far as to make everything from scratch. Hah! I’ve always attributed this loosely to the fact that most Americans over 40 descend from food-ignorant ethnic groups like mine (Anglo-Saxons). We value food as little as we value family integrity in this country. Cheap food and broken families mean more alienated consumers for the snack food marketing machine to inhale and 'influence' without 'annoying' gatekeepers like a) cash flow or b) Mom getting in the way. Soooo annoying.

A Symbol In Transition - The 2000s

Before the mainstreaming of organic apples, spinach, and potatoes in the 2010s, a major cultural shift happened in the world of milk that kicked off the transition of the organic symbol from a sign of environmental protection to a marker of class mobility and elite class status. And my fellow researchers witnessed it firsthand in the upper-middle-class pantries of America during hundreds of ethnomethodological interviews on how individual households entered the organic fray, purchase by purchase.

Milk always seemed to come first in the transition because it's one of the first things you give a baby after six months. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the retail acceleration of demand for organic fruit and milk had a lot to do with anxious, well-educated Moms feeding their babes and kids. These mainly were Baby Boomers and some Gen Xers.

As we interviewed these Moms, though, we noticed something. A deafening silence about the environmental benefits of organic agriculture: the voice of Gary Hirshberg was not audible in these kitchens.

Instead, what we heard, again and again, were rumors and fears about what bovine growth hormone might be doing to their babies, their kids, and their daughters. Fear of premature puberty, I kid you not, was spreading like a grassfire in the social networks of Whole Foods Market moms nationwide. It came up so often I swore that the N.Y. Times had written something about it. Nope.

What had happened was a classic word-of-mouth movement from the fringe edge of natural foods, including some staff at Whole Foods at the time. In 1995, the U.S. dairy industry began rapidly deploying rBGH, a synthetic growth hormone, to boost dairy production per cow (thereby boosting farm profits). Before the advent of social media, this single intervention into our milk supply, before broadband internet streaming scare videos and before YouTube, terrified hundreds of thousands of highly educated Moms. And they took action not only in milk but also in yogurt.

Yes, Gary, thanks for all the organic yogurt. But paranoid Moms made you wealthy, not environmentalist shoppers. Just let it go. It’s all good.

At the same time, 'organic' produce consumption spread very quickly in educated zip codes. The prime vehicle was the publication of famous lists like the 'dirty dozen' on websites and in print periodicals sold at places like….Whole Foods!7 And the focus there was the same thing that Hugo Chavez had been screaming about for decades - chemical pesticides soaking into your kids' food and doing God knows what to 'my farm worker brothers'? It was reasonable at the time to be skeptical that a male CEO at Monsanto or Bayer was somehow concerned about your kids' long-term health. Probably not an item on their prayer cards.

By 2005 or so, organic had transitioned into a modern symbol of 'purity.' Yet, this was not spiritual purity per se. It was very much a medicalized notion of purity, reducing exposure to environmental toxins that threaten to harm our kids.

And that's when things got a bit ugly.

How?

Well, if a small group of Moms is going to go around implying that their kids' diet is purer (i.e., 'organic') than other kids' diet, surely this won't go over well with the majority of Moms. Right?

Sure enough. Major media began writing about “elitist” organic consumers around the last Great Recession, partly because of the substantial price premiums on many, not all, organic items. This was also when the media picked up on the 'Whole Paycheck' gossip.8

Around that time, my colleagues and I discovered that of all the shoppers at Whole Foods who complained the most about Whole Foods prices in qualitative research samples, it was the heavy Whole Foods shopper who did it the most reliably. They were new to paying 80% more for all their groceries at the time. They converted real hard because the stores were beautiful and hip AND because many organic fresh items were just not available yet at mainline supermarkets. I would imagine these early converts have become used to the pricing by now. For those who convert rapidly to heavily organic shopping, it's a rude shock, the first set of receipts. And yet, they never seem to backslide. “Honey, things are tight, let’s just take the pesticide hit again, so we can afford our Starbucks lattes.”

There are many stats about how most U.S. households purchase organic items yearly, i.e., 80%+. Organic advocates cite similar research to show that organic food consumption is mainstream. Woo hoo! This is very misleading, though, because only one organic purchase counts in these surveys, and several of the top-selling organic categories involve items that tend to taste vastly better from smaller, organic farms with less depleted soil (e.g., apples, potatoes, corn, and berries). Infrequent, indulgence-related organic trade-up is a thing and may make up a significant % of low-frequency organic households. I don’t know of anyone who has even looked at this question.

So, if we want to know what organic means as a cultural symbol, it's essential to look mostly at households where organic is a hefty % of their groceries.

In 2017, only 8% of U.S. households purchased 50% or more of their groceries in natural or organic form.9 It's a small group that are this committed. Honestly, it's tough to be this strict because you won't be eating many highly processed foods (where you will still not find organic options). It takes shopping commitment beyond the variable of disposable income to absorb these premiums. There's the social effort required to be this consistent. A gentle and loving circle of accountability helps a lot: "Honey, you bought sh*t blueberries again. Stop it! You never listen to me."

A primarily organic household is one where organic is the default choice in dairy and essential produce items (i.e. the dirty dozen). This signals a strong commitment to minimizing exposure to chemical pesticides and fertilizers. And this commitment is, as I said, about maximizing dietary purity in a modern sense.

Organic : Pure :: Conventional : Polluted?

I've wound my way to this final section, where we confront the social science laws of dietary pollution rules. Try British anthropology’s masterpiece by Mary Douglas - Purity and Danger, is you want a deep dive. Historically, many societies have instituted strict dietary laws to separate themselves as superior to surrounding groups. Contrary to the bad narration of the Palestinian-Jewish conflict in Israel. This conflict extends as far back as the ancient Hebraic Kosher dietary rules, meant to distinguish Jews sharply from their Arab neighbors. And not in a jocular manner, I might add.

Such dietary elitism was very apt for Indian brahmins before the 21st century. Avoiding pork and beef, if not all meat, is still considered the diet of India's elite castes ( or anyone who wants to pretend to be a member!), those who not coincidentally dominate India's financial elite in the major urban centers. Brahmins historically believe that meat is polluting and defiling, like touching money. Moreover, many brahmins still believe meat-eating makes you angry and violent (!). There's a cure for homicide? No, sorry. FYI - most Indians eat meat; they just can't afford to eat it regularly. Vegetarianism is, therefore, NOT a Hindu practice; it's a caste-specific practice, devolving into a family-level practice.

Ancient forms of dietary elitism based on avoiding impure substances and polluted edibles may seem quaint or sad to us until you consider the rise of heavy organic eating households (like mine).

However, there is an essential nuance in modern forms of dietary purity behavior. We aren't that rigorous. At all. Not like conservative brahmins or Hasidic Jews.

As a medicalized form of impurity, Americans are open to the idea that a little bit of straying from the organic standard will a) not kill us and b) not cause us to lose all our friends.

The lack of any strict application of this new purity rule - organic= strikes me as perhaps the best proof that 'organic' is an optional but compelling and very loud marker of educated elite status in America today. It will therefore be attractive to a) established, educated elites who desire to appear modern badly and b) upwardly mobile middle-class folks who want to be like the former.

Purity in the form of heavy organic usage is still a social rarity, a marker of distinction as a modern, healthy person ‘who knows better.’ Oh, there we go again.

https://fortune.com/fortune500/2017/whole-foods-market/

Supermarkets have become much more profitable since the pandemic, but for decades barely made any money at all. https://www.fmi.org/our-research/supermarket-facts/grocery-store-chains-net-profit

https://agcensus.library.cornell.edu/wp-content/uploads/2007-Organics-Survey-ORGANICS.pdf

The USGS monitors water pollution from pesticides routinely in urban and rural areas. For more info, visit here: https://www.usgs.gov/mission-areas/water-resources/science/pesticides-and-water-quality

USDA

https://www.usda.gov/sites/default/files/documents/Reganold.pdf

https://peacewellnesscenter.com/Portals/0/Documents/Nutritional%20Guides/Organic-Foods.pdf https://www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna7758633

https://slate.com/culture/2006/03/the-dark-secrets-of-whole-foods.html

Hartman Group Food Shopping in America 2017 Study

"Mackey was pretty much the textbook definition of a Baby Boomer' hippie,' although the Austin Texas sub-variant." <-- thanks for this helpful identifier, James! As NH transplants in TX ... we never quite came up with this one, ourselves. Yeah, that's the ticket.

Lotsa funny questions and ideas in this piece!! Good points and proud to say i swore off WF before amazon swallowed it whole... tho it was a long process over the past nearly 3 decades down here. Met a family farmer at a local farmers mkt up in NW TX who said they were NON-certified organic... which i loved! Perfect! Supported them until we (thankfully!) left that area.

We very much miss our smart and funny NH people... and their/our yank-ified views... so different down here with the sub-variants among the uuuhhhh... cheeto-heads. HA!! :D

However, freezing my butt 10 mos a year... and getting chewed by black flies and mosquitos the other two months ... living for those occasional sunny, warm days... not worth it. Ya cahn't get theah from here, y'all... tho maybe y'all could try coming down here... brighten up the place as dour New Englanders?? :D