America's Elite Problem - It's All in the Definition

Ever since the Great Recession of 2008–2009, national media outlets and think tanks have reported on the growing income inequality in the United States. Yet, the problem is more complex and troubling than just income inequality. Regulatory or tax solutions alone will not be enough to address inequality on the scale it is now occurring. Inequality is always about far more than money. Especially the kind of inequality we’re seeing now in the United States.

When I began my second career — in market research- in 2003, one of my first clients was Whole Foods Market. At the time, food industry veterans mocked the chain and its ‘revolution’ in quality standards for the American pantry. Some even openly predicted that ‘organic’ was a pretentious fad that would blow over when the overheated economy reset. Most of these naysayers were white men in their 70s (now either dead or in their 90s). I bring this up because they represented the last generation born before America’s educated elite underwent a dramatic sociological and demographic transformation.

The economy did bomb in 2009, but the organic food revolution kept growing right through it and has now only become more extensive in scale. As a field researcher for the food industry at the time, I noticed something in the home pantries of Whole Foods Market’s heavy shoppers (they call them the ‘Core’ shopper internally). These folks were both affluent and educated and almost always Moms with young kids. These young families reminded me of my own, growing up in Bedford, NH., in the 1980s. Except for one thing: the Moms were more likely to be post-grad educated, not just college degree holders. And they had lots of questions about people in authority. Not all of them were friendly questions either.

It made intuitive sense that affluent Moms would now gravitate to premium food choices simply to maintain social status. Yet, this didn’t fully explain what I saw in the field since I kept hearing a health-related critique of the American food system. This critique took off with the assault on hormones in milk and the parental fears it ignited among Whole Foods Moms. This fear fed off increasing distrust in America’s central institutions, distrust by educated elites themselves. All that education of Baby Boomers and Generation X generated a much larger group of critical thinkers who were unwilling to take institutional pronouncements at face value.

After the birth of our first child in 2007, I found myself joining the ranks of Whole Foods Market core shoppers as a participant observer. And I became fascinated with the sheer amount of money a Whole Foods Market Mom spends each month on groceries. So, I started collecting our receipts as a non-representative but directional case study. And I was shocked to discover we were paying five times the annual grocery bill of a typical family of four at the time (per the available BLS data).

That’s some class privilege for sure. But I assumed my home represented less than 1% of America who wanted to and could afford to live like this. But was I such a rarified snowflake?

Five years later, in 2012, my consulting team and I looked into a related hypothesis triggered by Pew Research data on the shrinking middle class. Our publicly-traded client base was concerned about stalled growth and shrinking household reach of their brands. We suspected that a steady increase in organic and premium food consumption, and declining purchase of formerly iconic food brands, reflected mobility upward into the ranks of the upper-middle-class elite.

So, who is this upper-middle-class elite (or upper class)? Well, social scientists generally like to use the concept of SES (socio-economic status) when analyzing class issues. As the acronym implies, they use multiple variables to define various social classes, not just income (as you see in the media and business).

So, the team I led back then used a) educational attainment and b) income as the components of our SES model. It yields about nine or ten SES segments, depending on how you define things. Why did we pick these two variables? There are a couple of reasons. 1) these standard demographic variables allow anyone else to connect the findings to many other databases since these two demographic variables exist in most surveys. But, most importantly, educational attainment is critical because we know it leads to different consumer choices, especially as you approach the extremes of privilege and underprivilege. Since 70% of our economy derives from these choices, it’s critical NOT to assume that adults with similar incomes behave similarly in everyday life. I know from prior corporate research that brand preferences tend to exhibit substantial divergence at the extremes of educational attainment, regardless of income. Education better predicts consumer choices than mere income levels. I learned this touring the pantries of America in person. So, I believe it’s critical to intersect education with income to understand better how we make big decisions, like who we live near, and small decisions, like how expensive our produce is. It is the unconsciously held rules behind all these decisions

Using these two variables, I originally defined the upper-middle-class in 2012 as the following: 4-year college graduates with $100K or more in 2012 household income. Notice that this definition deliberately avoids a narrow focus on the 1% over which the modern media loves to obsess for rhetorical impact.

And when my colleagues and I looked at this group in Census data, adjusting for inflation, we found it had doubled in size from 1991 to 2012

This doubling of America’s elite was remarkable and helped explain the dramatic, double-digit growth of natural/organic consumer brand purchasing (our client focus at the time).

But what has happened since then to the upper-middle-class, roughly the same group David Brooks popularized in his fascinating book- Bobos in Paradise? And more importantly, why do we care?

______________________________________________

As part of my initial research project for the Institute, I recently did a similar analysis of the upper-middle-class. This time, though, I raised the class ‘membership’ standard and analyzed the group as individuals, not households, with $100K or more in 2019 total personal income. Raising the income threshold allows us to see a tighter group of adult individuals who have more than enough income to live in nice apartments or homes and buy lots of discretionary goods and services.

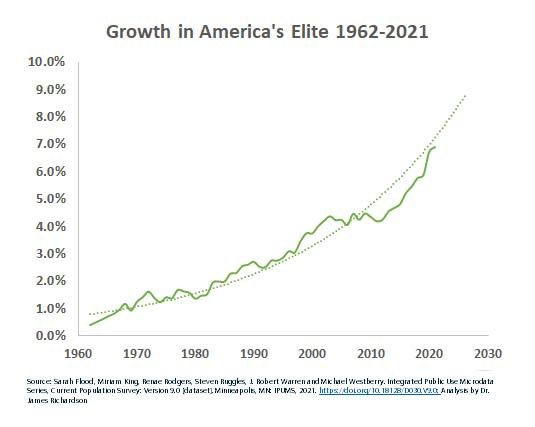

For this updated view on the growth of the upper-middle-class, I had access to a 60-year chronicle of Census data from 1962 until 2020 (w/help from IPUMS at the University of Minnesota). When I ran the raw line graph last November, I nearly fell off my chair. I initially hypothesized that the upper-middle class had grown primarily in the 1990s and early 2000s. In fact, in 2012, I just assumed the growth in the size of America’s elite would decelerate. After all, the economy already appeared overheated coming out of the Great Recession.

However, the long-term growth of the upper-middle class, adjusting for inflation, actually accelerated during the 2010s. I was too busy changing diapers to notice. America’s elite inhaled millions more Generation X and Millennials, mainly born into middle-class families. It is now 7% of the U.S. population or twenty-three million adults 25 and over. That’s the same size as the state of Florida population or the seating capacity of 353 large-sized NFL stadiums!

Instead of the mythic rags-to-riches journey the media still loves to highlight, especially with immigrants, this journey never happens. The most recent longitudinal studies tracking class mobility in real-time (with a fixed cohort) indicate that only 6% of Americans born into the bottom income quintile make it to the top quintile (Source: Getting Ahead Or Losing Ground: Economic Mobility in America, 2006, p. 19 Figure 5, Brookings Institution).

All of the inter-class social mobility in the last half-century appears to have been from the middle-class to the upper-middle-class. As you’re reading this, like me, you can probably list off a bunch of relatives who experienced this dramatic journey, maybe even yourself — climbing from the middle to the upper-middle-class sounds like a less cinematic American dream but a good outcome., correct?

______________________________________________

Why should this exponential growth in the upper-middle-class concern us as a nation?

There are three big reasons, but they are probably not the only ones. 1) The elite has become a functionally endogenous social world in everyday life. Members don’t have to interact with ordinary Americans. They are large enough to develop internal schisms operating at a large scale. 2) Most venture capital funding any innovation focuses on servicing the elite at the expense of social cohesion and public infrastructure investments. 3) This elite shares a core value of hyper-individualism, making them more distracted than any other elite group in history from the social forces influencing them.

The Inward-Focused Elite — the class stratification of American neighborhoods and zip codes allows most elites to spend their free time mainly in the company of similarly privileged adults. They also work in companies primarily composed of similar elites (i.e., not just the executives). They can hang out in coffee-house third-places full of the similarly privileged. Today, the American elite is so vast that it has developed multiple internal schisms, not all overtly political. Yet, what the Whole Foods elites of the 2000s made me realize at the time was that there was a large macro-schism emerging within the American elite. It was dividing the media. It was dividing elite zip codes, even neighborhoods. The schism is between a) ‘left-leaning’ elites favoring individualist techno-modernism instead of social tradition and b) ‘right-leaning’ elites trying to return to an imagined patriarchal past of strict gender roles, limited class mobility for non-whites, even white supremacy. The first group anchored itself in an optimistic future free from the constraints of tradition. The second group arrived in an imagined past, a nervous reaction to multi-factorial social change they find offensive. And in the middle are millions left undecided and confused by both of these divergent perspectives on which way we should be looking: to a hyper-individualist future or a neo-communitarian past. The ‘elite’ is now so enormous that it is more than capable and highly likely to fight internal battles to control our significant institutions; and deploy less ambitious elites and, more importantly, the broader population as mere pawns in intra-elite power struggles. It was far easier for this elite group to get along when it was a minuscule proportion of the population and when 99% of Americans didn’t fit into it. It is the HGTV class. And it’s enormous!

Innovation for Elites by Elites– Elites represent a large audience that consumes more per capita than other SES groups. It is not surprising that most venture capital-funded innovation aims at products and services with these folks as the initial core audience. I don’t see anyone investing in fintech solutions for the unbanked or appliances for use in housing projects where the goal is minimal electricity usage. In consumer products, the innovation audience is usually the same elite subworld as the founder, and if it takes off, it spreads to the middle classes through price reductions. Looking at the Top 10 2021 unicorns, we see that the majority are services most valuable to well-capitalized elites — Instacart, Stripe for small business owners, SpaceX, Canva, and Databricks. In consumer-packaged goods, almost all the funding goes to premium-priced innovations that re-frame existing offerings as inferior in quality (to some audiences). Elite concerns with quality of life, finance/wealth management, and techno-futurism best explain the underlying, non-financial motives for the narrow concentration of funding into IT, finance, healthcare, and consumer products (Source: CB Insights. These cultural domains attract the imagination of elites who have the luxury to contemplate and imagine alternative or ‘better’ futures for themselves (and for others who do not do the initial imagining). This is another reason why elites talk incessantly in business about ‘visioning’ and ‘vision-setting.’ This is a class of people freed of any survival-related issues at all, able to live, like the aristocrats of yore, inside their imaginations and to make those imaginings real (e.g., through innovation). There is no evil intent per se, just an unusually privileged set of base conditions for this degree of future-leaning imagination to become a lifestyle for 23 million adults (see above chart). And to inspire similar thinking among equally well-educated people.

Hyper-individualism Focused on a Personalized Future — David Brooks’ popular ethnography of the upper-middle-class in the late 1990s focused on the seemingly unlimited capacity for Bobos to parse nuances of distinction that they didn’t care at all about even ten years prior. Bobos led a revolution in redefining ‘high quality’ in hundreds of consumer categories starting in the 1990s and continuing through this day. Almost all of these new products reflected emerging values within a portion of the upper-middle-class elite. When I step back, though, most can roll up into very elitist buckets: greater longevity, higher quality of life, elite fitness, thin/skinny body image; the list keeps growing. These newer values or objectives rest on a more fundamental cultural ideology or version of it: hyper-individualism. It continually optimizes life choices for something better, more contemporary, more modern. It is a class ideology anchored in the near future with its sights set way into a future that upper-middle-class people intend to get better and better. Hyper-individualism is not about actually being unique or acting solipsistically. It’s about optimizing and refreshing/updating choices that have just become habits as much as you can until you run out of energy or time. And we all do.

What are the social questions raised by America’s exploding elite?

I do not think it is harmless that a society develops a large elite group this vastly more educated and wealthy than the majority it lives near but with whom it does not interact in any meaningful way. An elite living among Americans but only with transactional monetary relations to the broader public. An elite whose consciousness lies anchored in a personalized, optimized future state and how to get there.

The questions this group raises include, but are not at all limited to, the following:

How do we reconnect elites to ordinary Americans whom they almost never meet?

What constraints on individual freedom need to emerge in the media and finance spheres to prevent toxic misuses of individual freedom?

What forms of new, inclusive community can be created to keep the elite in check?

How do we defend against elite misuse of populism to fight intra-elite battles?

How do we shrink the elite to strengthen the majority?

How does America avoid a neo-nationalist (and likely tyrannical) solution to intra-elite conflict between the old and future order of things?

Perhaps we can start from here to clarifying the subdivisions of the elite? https://archive.is/aWliq https://www.swyx.io/breaking-barbarian https://archive.ph/1G2uz

Here I see at least 3 different definitions: The 1% ("upper class" elites, 300K+ USD salary), the 5% (upper gentry "rich" + elite "ultra-rich", 100K+ USD salary), The 20% (SME "owners" + UMC/PMC+ elite, 50K+ USD salary). The 1% mainly has Ivy League connection, the 5% includes also non-Ivy graduate high performers with high autonomy, while the 20% are the bulk of college graduates with or without autonomy.

This line of thought can hopefully transfer from generation to generation. 10% of ancient Japanese people were Samurai, about 10% of the French people before the revolution were either aristocrats or bourgeoisie, and about 10% of internet communities are contributors (including creators and critics) rather than passive consumer-gossipers. https://archive.ph/7YAa8

Applying Danco's typology (cross reference ACX), the 1% is eccentrically invested in politics, the 5% is Bohemian in its provocative speech, and the 20% are outraged hippies of bipolar political factions. https://danco.substack.com/p/michael-dwight-and-andy-the-three https://astralcodexten.substack.com/p/book-review-fussell-on-class/comment/1350556 https://astralcodexten.substack.com/p/book-review-fussell-on-class/comment/1358393

When this is done, should the future elite be pegged to wealth distribution quantiles (hard to tally)? multiple of median income (undermines absolute poverty)? multiple of average income (overreport size of elite in "good times")?

Excellent article. Really enjoyed your in-depth analysis.